Real Fictions, Fictitious

Realities

by Thomas Wulffen

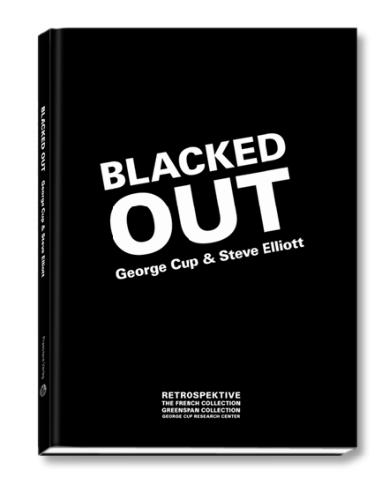

in: Catalogue: Blacked Out - George Cup &

Steve Elliott - Retrospective, Berlin 2008

The country of Transnistria was recently the subject of a report in

Deutschlandradio. This was not an examination from a literary

perspective, but instead a journalistic report about Transnistria’s

struggle for international recognition. For eighteen years, this tiny

country not so far from Odessa has existed after declaring itself

independent of the Moldavian Republic. Transnistria is not recognized

by any other country and exists only for the inhabitants of Transnistria

itself. What status does the nation of Transnistria possess for those

who are not its inhabitants?

During the course of the theorizing about the structure of matter in the

field of atomic physics, the English atomic physicist Peter Higgs

conceived of the so-called Higgs particle, also known as the Higgs

boson, whose existence has up till now not been proven. With the

help of this construct it is possible to resolve contradictions in the

Standard Model. If no trace of the Higgs boson is ever found, then the

Standard Model is false.

In 1973 there appeared in the collection of texts Idea Art edited by the

art critic Gregory Battcock a short text about the artist Hank Herron

entitled “The Fake as More,” written by Cheryl Bernstein. Only thirteen

years later was the text exposed as a fabrication and fiction by the

critic Thomas Crow in his article “The Return of Hank Herron.”

These examples bear witness in various ways to the function, impact

and significance of fiction. The example of Transnistria is situated on

the level of fictional objects in political space. Even if this state exists

as such, on the one hand its non-recognition denies legitimation to its

existence. But on the other hand, self-assertion is a fundamental

element of every national order. The justification for the invasion of

Iraq by American troops in 2003 largely consisted of a fiction based

on the existence of weapons of mass destruction asserted to be in the

hands of Saddam Hussein. The point of departure for this undertaking

was information furnished by a BND agent with the alias “Curveball,”

whose credibility was already subject to doubt beforehand, but whose

assertions fit conveniently into the political calculations of the Bush

administration. In political controversies, fictions are again and again

declared to be realities, in order to be able to defy one’s opponent.

In the field of science, the use of fictitious objects is a more or less

legitimate means of scientific investigation and university debate. If

inconsistencies or contradictions arise in a given system, they can be

temporarily abrogated by the deliberate utilization of fictitious entities.

The aforementioned example of the Higgs boson is one instance of

this. But at the same time there is an indication here that a fictitious

object can become a real one. This does not, however, allow the

reverse conclusion that a real object can become a fictitious one.

Or could it be that we have here underestimated the significance of

literature as an essential part of culture and art? In literature, there

occurs the conversion of a real figure into a fictitious person. A famous

example of this is the novel Buddenbrooks. Verfall einer Familie

(Buddenbrooks. The Decline of a Family) by Thomas Mann, for which

the history of the author’s own family served as the basis for the plot

of the novel. What status does the figure of Tony Buddenbrook

assume with regard to the model Elisabeth Mann? Is it not

permissible in this case to proceed from the assumption that the

figure of Elisabeth Mann takes on representational elements from the

fictitious figure Tony Buddenbrook which are capable of effectively

changing the real person?

In the contemporary highly complex societies of post-industrial

nations, it may be considered as a given that their manners and

means of identification are based on both so-called real and fictitious

attributions. There where the dividing line between fact and fiction is

scarcely perceptible any longer, the personality as well comes to be

blurred in its situation somewhere between fact and fiction. Who is

Brad Pitt? Who is Hank Herron? The latter can be reconstructed on

the basis of the text by Cheryl Bernstein. But who is Cheryl

Bernstein? For her part, Cheryl Bernstein is a figure penned by the art

historian Carol Duncan who, together with her husband Andrew

Duncan, developed the figure “Hank Herron.”

This story, in the double sense of the word (translator’s note:

Geschichte, “tale” or “history”) has been repeated on various levels

and can itself make reference to a sort of model. Stefan Koldehoff’s

book entitled Meier-Graefes van Gogh is subtitled Wie Fiktionen zu

Fakten werden (How Fictions Become Facts). In 1998 William Boyd

wrote the story of Nat TateÞAn American Artist 1928-1960. Behind

this quite successful fiction (the text is complemented by photographic

material on the life and work of Nat Tate) stand not only the man of

letters Gore Vidal but also the musician David Bowie. In 1993 Warren

Neidich discovered the “unknown artist” and, in a book of that title,

situated him in the context of art history. But in fact this artist only

constitutes a part of art history to the extent that he comes to the fore

as an aspect of familiar depictions of artists’ meetings. It is also a

matter, however, of an ironic self-image of Warren Neidich, who

himself plays the unknown artist. The oeuvre of Dirk Dietrich Hennig

is simultaneously a mirror and a repository for the theme of fiction and

fact in the field of contemporary art on the level of the person, the

archive and the operating system which is art.

“Must Art History Be

Rewritten?” – In Place of a

Preface

by Roland Nachtigäller

in: Catalogue: Dirk Dietrich Hennig / Blacked Out

- George Cup & Steve Elliott - Retrospective,

Berlin 2008

When a comparatively young institution such as the George Cup

Research Center, which moreover claims to have offices in New York

and Hannover, approaches two rather small exhibition institutions with

the suggestion of a thoroughly sensational project, then as a rule

caution is required: How serious is this sort of organization, whose

interests possibly lie hidden in the background, how is the research

center financed, and with what scholarly pretensions is work being

done there? Generally these are questions which can only be

answered with difficulty down to the last detail, and to which one

responds – after some preliminary research – more or less intuitively,

on the basis of one’s feelings in encounters with individual persons,

and with a view to the existing or absent fascination engendered by

the specific artistic project.

So what is the appropriate attitude when an eloquent individual in his

mid-forties arranges with the requisite circumspection a personal

appointment with the secretarial office and then, in a jovial and self-

confident manner, proceeds to serve up an almost unbelievable

story? In this case the biography of an American artist-couple with

German roots, whose name in Europe (in the meantime!) is almost

completely unknown, but who nevertheless are supposed to have

belonged since the early nineteen-sixties to the most influential

impulse-sources of American Minimal Art: George Cup & Steve

Elliott? Two artists and in addition, for more than thirty years lifetime-

companions, whose respective and joint works were not only slowly

forgotten during the last twenty years, but were supposedly also

systematically removed from collections and art-historical

examinations?

Above all after a careful examination of the works in question, and

after due consideration of the numerous aspects of this enigmatic art-

historical originality, the Städtische Galerie Nordhorn and the

Kunstverein Wolfsburg decided to present, as the first institutions in

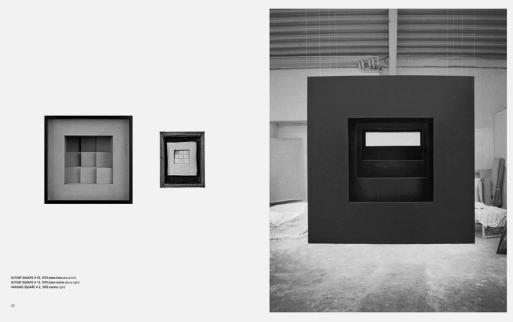

Europe, the two-part retrospective of both artists. The works are

drawn from two different private collections, which up to now have

likewise not appeared in a more extensive framework – the collection

of a French enthusiast who remains anonymous here, and the

collection of A.C. Greenspan – whose convincing work-groups by

George Cup & Steve Elliott ultimately tipped the scales favorably. It is

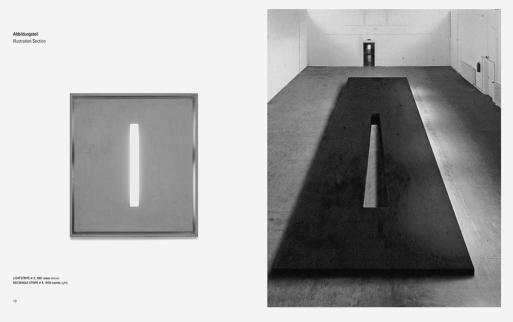

above all the great artistic energy, the unswerving focus of the

Minimalist attitude in the struggle for formal reduction (here above all

in terms of color), and the so-called primary structures which

persuaded the responsible officials to take a chance on this

experiment consisting of an exhibition whose validity cannot be

guaranteed one-hundred percent. Ultimately of pivotal importance

were also discussions about how much the individuality of the artistic

position actually comes to the fore in a lifetime oeuvre which

conceives of art above all as a depersonalized, self-referential

system. If then in later years, for example, this de-individualization,

the attempt to avoid all allusion to everyday objects, or a deliberate

anti-illusionistic procedure are slowly retracted, then to what degree is

there the actual emergence of a productive “slapstick potential of

Minimal Art” (Jörg Heiser, Plötzlich diese Übersicht, “Suddenly This

General View,” 2007)?

Thus there are above all questions at the beginning as well as at the

end of this preparatory process, and in this case these are

predominantly inquiries which are directed more towards the public

than to the respective institutions. Why were these groups of works,

which seem so consistent within themselves, not acknowledged for so

long a time in an appropriate manner? With the rediscovery of these

works, is there a concomitant change in the view of Minimal Art

altogether? Which interconnections emerge into view here between

the Constructivism of the nineteen-twenties, the tendencies of

American abstraction in the post-war years, and the post-avantgardist

movements of the nineteen-eighties? Must evaluations and

correlations, art-historical classifications and perspectives be

rethought?

And finally, this exhibition, its history and its objects also rests upon a

fundamental issue: How does history, how does art history arise? “No

pause for breath; history is made, it moves onward” (Fehlfarben,

1980). But then who makes history? Every individual, opinion makers,

the mainstream, or market interests? And how objective is this

history? There have been periods when the focus of classical history

was primarily on revealing the wide panorama of dominating interests,

and a start was made in writing a new history “from down below.” At

the moment, however, heroes are once again being sought, in art as

well. And only too often one hears the prescription that history must

be “rewritten” or even entirely “written anew.” By whom? For what

reason?

Ultimately it is a question of responsibility as to which exhibitions and

which works are presented to an interested public by communal, or at

least non-commercial, exhibition institutions. The generally interested

visitor, just like the professional public, trusts that a fundamental

seriousness and purity constitute the basis for the works being shown.

And so in the end, it is also a question of individual passion when, in

two institutions which are actually dedicated to contemporary art,

there is a presentation of this in no way risk-free view of the historical

works by George Cup & Steve Elliott. Available as formal justification

are the astonishing urban-historical correspondences of their

respective birthplaces (in Nordhorn and Heßlingen, today Wolfsburg),

but in this matter both institutions have their backs to the wall. If we

present this artistic duo and their works for discussion, we allow the

audience, each individual person as well as the professional world, to

form an opinion – not only concerning the relevance, quality and

binding character of the exhibited works, but also as to whether we

have become entangled in the complex web of various hidden

interests so that, upon more exacting scrutiny, everything turns out to

be utterly different…

Roland Nachtigäller, 2008

Catalogue:

Blacked Out - George Cup & Steve Elliott

Retrospective

with texts by A.C. Greenspan, Justin Hoffmann,

Thomas Mang, Roland Nachtigäller, Lutz Stratmann,

Thomas Wulffen

in german and english

55 pages with 47 images in hardcover

Praestare, Berlin 2008

ISBN: 978-3-922303-64-0

© dirkdietrichhennig.com 2024