A Reconstruction

by A.C. Greenspan

“I don’t give a shit when the shit hits the fan.”

George Cup, 1977

“That which is intended for the eyes can’t be explained to the ears.”

Steve Elliott, 1980

There are artists who suddenly disappear from the field of vision of the

art world, although they had an exemplary significance for their

contemporaries. The artist-couple George Cup & Steve Elliott represent

one of those cases. Only a small group of art collectors and friends,

among whom A.C. Greenspan count himself, has preserved their

memory during the last twenty years.

George Cup was convicted in 1986 for the alleged murder of his

romantic and professional partner Steve Elliott and was imprisoned in a

New York penitentiary. As a consequence, the oeuvre of these two

artists, who numbered among the founders of American Minimal Art,

was almost completely “erased.” In recent years, no one believed that

their oeuvre would experience a belated recognition some twenty-two

years after this grievous error of justice.

It is above all due to the initiative of the George Cup Research Center,

established in 2006 with offices in New York and Hannover / Germany,

that the works of the two artists have be seen in Germany for the first

time since their last exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York

in 1985.

In a dramatic manner, George Cup’s state of health deteriorated so

extremely during the preparations for the exhibition that in July 2008,

two months before the opening in Wolfsburg / Germany and barely a

year after his name was cleared and he was released from prison, he

died at the age of seventy-eight.

The family of George Cup, who was born in 1930 under the name of

Georg Anton Kupsch in Heßlingen, the city which today is Wolfsburg,

immigrated in 1936 to the United States and settled in New York City.

Steve Elliott, born in 1933 in Nordhorn / Germany under the name

Stefan Berliott, grew up at only a few miles’ distance from George Cup,

on the other side of the Hudson River in New Jersey. The two met in

1954 at the Art Students League in New York, where Steve Elliott was

studying. At this point in time, Cup was still pursuing his ambition of

becoming an architect, but he definitively abandoned these plans in

1960. Designs dating from 1956 for a house shaped in the form of a

cube and covered in black slate slabs, however, already provide

indications of his subsequent artistic development.

As is typical for many artistic couples, George Cup & Steve Elliott were

connected by an ambivalent relationship. George Cup had an

uncontrollable temper and was known for his quarrelsomeness,

resistance to compromise, and aggressivity. Robert Rauschenberg

even described his imprisonment as the logical consequence of his hot-

tempered character.1 And A.C. Greenspan increasingly came to view

Cup as unpredictable. One time in an exhibition, he spit and urinated

on works that displeased him; during disputes he knocked glasses from

the hands of gallerists, or he stomped to pieces his own works which

had already been sold. This sort of behavior may have a positive effect

on the image of some artists, but not with Cup and Elliott. According to

Betty Parsons, “…everyone took offense at his arrogance,”2 and Andy

Warhol stated repeatedly, “He’s an asshole,” and added, “an asshole,

but a handsome one.”3

Steve Elliott, on the other hand, appeared to be the exact opposite of

the eccentric personality of George Cup. He was introverted and

always courteous when A.C. Greenspan visited him in his studio, where

he could be found day and night, whereas George to a large extent

made his appearance alone or in the company of other men in New

York’s gay and art community. Although the works almost without

exception were signed by George, many considered Steve to be the

actual creative and dynamic force of the couple. André Emmerich

described their relationship in 1974 “…as a fragile give-and-take that

had its ups and downs. George needed Steve for inner support and

Steve needed George for external representation.”4 Even if the

assignment of creatorship proves to be problematic in individual cases,

a comparison of the autonomous early works of Cup and Elliott with the

oeuvre of the artist-couple and the late works of Cup which were

created in prison demonstrates that two independent artists had found

in their mutual connection a “critical mass” which is perceptible even

today as a source of inspiration.

At the end of the nineteen-seventies, George Cup began for a while to

shift his chief place of residence to Paris. The reason for these stays in

Paris was the relationship to an “official Frenchy,” as he was

affectionately called by Cup. All the way down to today, it remains

unclear what individual was hidden behind this designation. Even the

George Cup Research Center remains discreet and speaks only of a

“respected personality from public life in France.”5 The foundation

established in 2006 by this unknown Frenchman has made available on

loan a majority of the works which are to be seen at the Kunstverein

Wolfsburg: “The French Collection.” Because the collection was stored

in a cellar in the Parisian arrondissement du Louvre and was exposed

to humidity, extensive restoration work was necessary in the run-up to

the exhibition.

“The French affair” was initially no more a burden upon the relationship

between Elliott and Cup than were the other affairs which Cup openly

conducted during his thirty-two-year relationship with Elliott, and with

which the names of John Cage, Andy Warhol and Robert

Rauschenberg have been linked. At the end of 1985, however, Steve

Elliott took what had become an inevitable step and moved out of their

common New York apartment. The separation thrust Cup completely

out of his unstable equilibrium. Attempts to clarify the situation ended

with Cup’s violent intrusion into the new apartment of Elliott, who

answered with a restraining order. The situation escalated in the spring

of 1986: Cup, who could no longer control his aggressions, was the

subject of two complaints for bodily injury after fights in New York clubs.

It was only possible to avert judicial processes through the payment of

damages for pain and suffering. These two events were of decisive

importance for Cup’s indictment and conviction when, three months

later, Steve Elliott was found dead in his New York apartment. The

media and popular opinion were unanimous in their belief that George

Cup has killed his partner. Thus even before the trial began, the New

York Post ran the headline “Cup Kills Elliott!”6 Eyewitnesses from the

neighboring building claim to have seen Cup at the scene of the crime

on the night in question. His extensively documented proclivity for

violence along with further pieces of evidence led to a lifelong

conviction, which he began to serve in November 1986 in a New York

penitentiary. During the course of his imprisonment, there began an

almost systematic “erasure” of the artistic works by Cup and Elliott.

Sculptures were disassembled and disappeared; works were removed

from the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the

Guggenheim Museum, and today they cannot even be found in the

inventory lists. Up to the founding of the George Cup Research Center,

it almost seemed as if the artist-couple had never existed. The reasons

for this radical sequence of events are puzzling and even today the

matter has not been cleared up, nor are any written statements by

responsible figures to be found.7

Even when surprisingly, at the beginning of 2007, George Cup was

able to prove his innocence with regard to the death of Steve Elliott

and, with no attention being paid by the media, was released from

prison as a free man, numerous questions remained unanswered. Why

had Cup not commented for twenty years concerning the events that

took place in 1986? Why did he continue to remain silent after his

exoneration? For whatever reasons he possibly held himself

responsible for the death of his partner, here as well he never gave us

an answer.

In the summer of 2007, the George Cup Research Center contacted

the artist and prepared, in cooperation with the two exhibition houses in

Wolfsburg and Nordhorn, Cup’s and Elliott’s respective places of birth,

a first inventory-taking of those works which, in addition to those from

the “French Collection,” were still available. Already in 1991 a storage

site in Brooklyn had been dismantled and its works destroyed. During

the course of its investigations, the Research Center became aware of

the collection of A. C. Greenspan consisting of forty-two works, most of

which are being presented for the first time in the Städtische Galerie

Nordhorn. The models and photographs of objects and installations

from this compilation were taken as the basis for the realization of the

exhibitions in Germany, which were conceived in close cooperation with

George Cup.

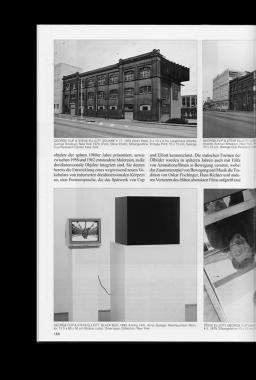

The large-format installation SQUARE-ROUND # 4, dating from 1973,

had been reconstructed for the Städtische Galerie Nordhorn according

to drawings and designs. Ten square wooden panels set up one behind

the other present to view a succession of ten squares cut out of the

panels, each varying by a few degrees so that in a certain sense there

is created a squaring of the circle, which is gradated from the black of

the first panel past various shades of gray to the white of the final

panel. This installation is characteristic of Cup’s and Elliott’s works from

these years. Reduced geometrical surfaces in various sizes which

nonetheless are always related to human dimensions subdivide,

individually or serially, the entire space, floor or wall. In spite of rigorous

structural clarity and monochromatic coloration, there arises a complex

interplay among open and closed volumes, internal and external forms,

object, space and viewer. In addition to the space-encompassing

installations, various wall objects combined with fluorescent tubes and

dating from the late nineteen-sixties are presented, as well as paintings

from 1956 and 1962 which are integrated into the three-dimensional

objects. They already point towards the development of a seminally

new vocabulary of reduced, three-dimensional bodies, a formal

language which is characteristic of the late works of Cup and Elliott.

The static forms of the oil paintings were set in motion in later years

with the help of animated films, so that the interplay of movement and

music, the tradition of Oskar Fischinger, Hans Richter and other

representatives of the early abstract film, was taken up and

reinterpreted. The connection between form and sound consists of

twenty-six animated films which were created between 1974 and 1979

on 8 mm film and which, because of their bad condition, have been

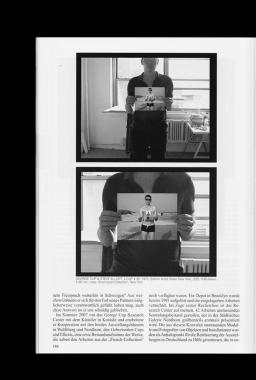

digitally remastered for the exhibition. In the experimental film Loop #

24 (1972), the camera zooms towards a photograph which Cup is

holding in his hands and which, for its part, shows Cup with a

photograph in his hands. For five minutes, the camera zooms in a

straight line through the sites depicted on various photographs on

different locations. Further animation films and kinetic objects, as well

as artist’s books and the video installation BLACK BOX # 2 from 1979

are distributed between the two exhibition houses and offer a

comprehensive view of the oeuvre of George Cup & Steve Elliott.

These first two exhibitions of the German-American representatives of

Minimal Art, George Cup & Steve Elliott, since their disappearance from

the field of vision of the art world hopefully represent only the beginning

of a new evaluation of their work. The future will show whether this

rediscovery of George Cup & Steve Elliott will remove the shroud of

silence from them once and for all and will assign to them their well-

earned status in the history of art.