Dirk Dietrich Hennig

by Roland Meyer

in: Made in Germany Zwei, Nürnberg 2012

For years, artist Dirk Dietrich Hennig has been working success-fully

on his own invisibility. He barely surfaces as author of his works,

preferring to assume the role of mediator, raising the visibility of

others: forgotten artists such as George Cup and Steve Elliott or Jean

Guillaume Ferrée, for whom he acts as curator, executor and

biographer.

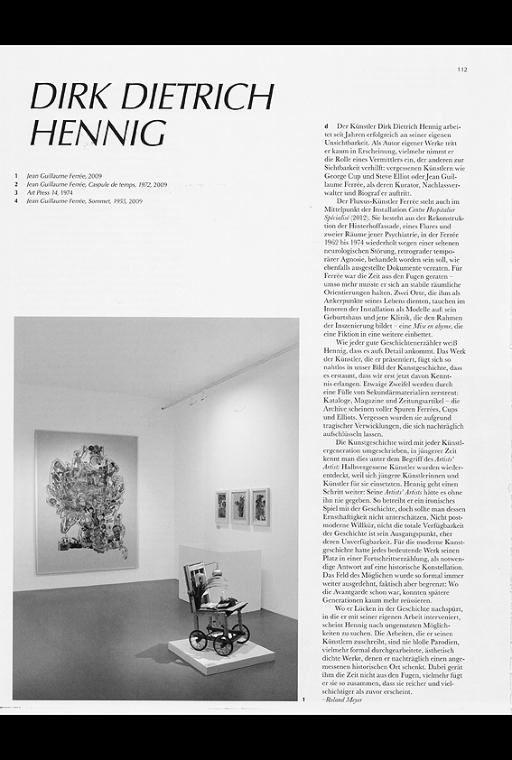

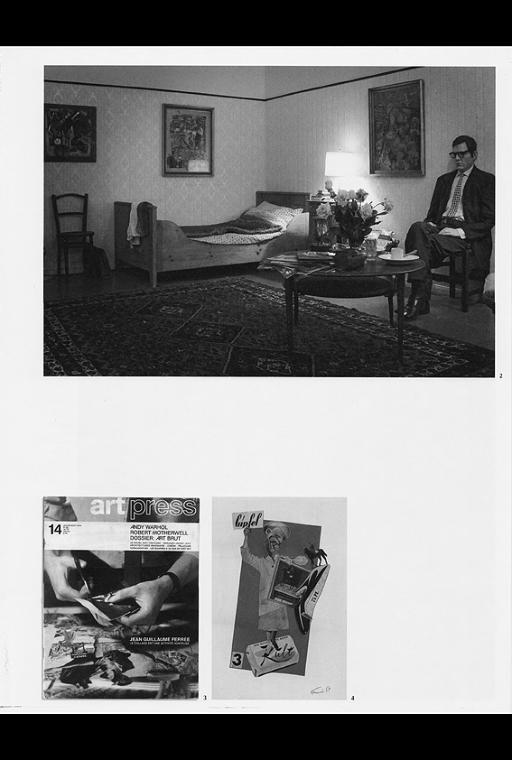

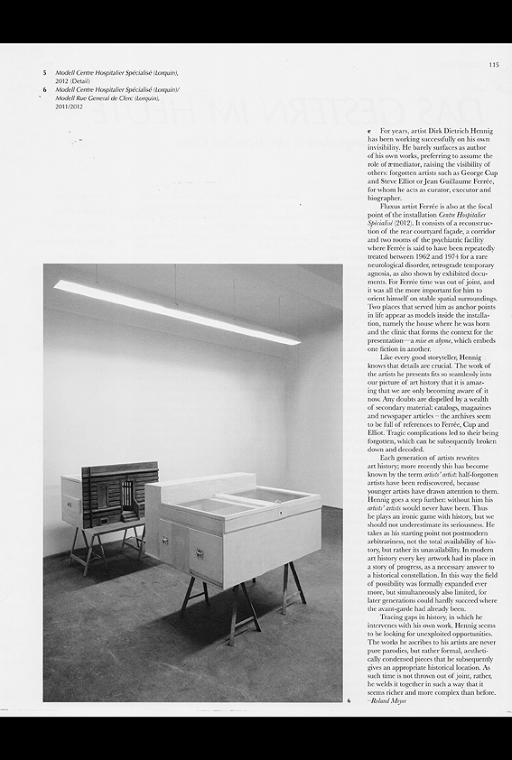

Fluxus artist Ferrée is also at the focal point of the installation Centre

Hospitalier Spécialisé (2012). It consists of a reconstruction of the

rear courtyard façade, a corridor and two rooms of the psychiatric

facility where Ferrée is said to have been repeatedly treated between

1962 and 1974 for a rare neurological disorder, retrograde temporary

agnosia, as also shown by exhibited documents. For Ferrée time was

out of joint, and it was all the more important for him to orient himself

on stable spatial surroundings. Two places that served him as anchor

points in life appear as models inside the installation, namely the

house where he was born and the clinic that forms the context for the

presentation-a mise en abyme, which embeds one fiction in another.

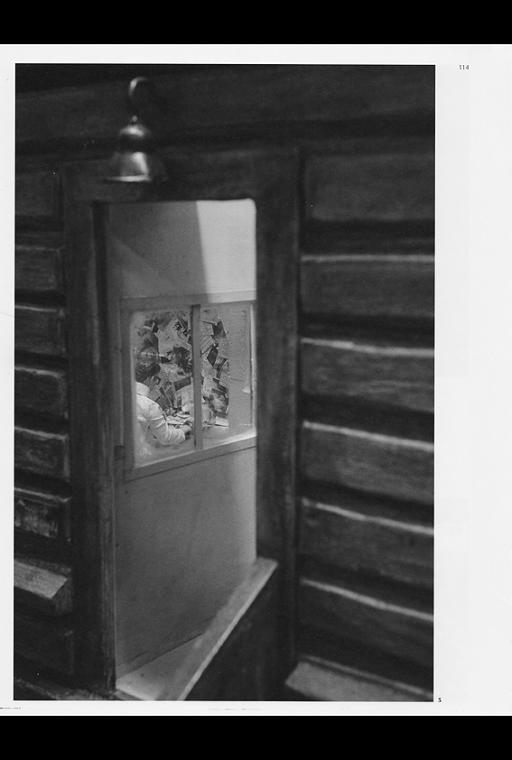

Like every good storyteller, Hennig knows that details are crucial. The

work of the artists he presents fits so seamlessly into our picture of art

history that it is amazing that we are only becoming aware of it now.

Any doubts are dispelled by a wealth of secondary material: catalogs,

magazines and newspaper articles – the archives seem to be full of

references to Ferrée, Cup and Elliott. Tragic complications led to their

being forgotten, which can be subsequently broken down and

decoded.

Each generation of artists rewrites art history; more recently this has

become known by the term artists artist: half-forgotten artists have

been rediscovered, because younger artists have drawn attention to

them. Hennig goes a step further: without him his artists artist would

never have been. Thus he plays an ironic game with history, but we

should not underestimate its seriousness. He takes as his starting

point not postmodern arbitrariness, not the total availability of history,

but rather its unavailability. In modern art history every key artwork

had its place in a story of progress, as a necessary answer to a

historical constellation. In this way the field of possibility was formally

expanded ever more, but simultaneously also limited, for later

generations could hardly succeed where the avant-garde had already

been.

Tracing gaps in history, in which he intervenes with his own work,

Hennig seems to be looking for unexploited opportunities. The works

he ascribes to his artists are never pure parodies, but rather formal,

aesthetically condensed pieces that he subsequently gives an

appropriate historical location. As such time is no thrown out of joint,

rather, he welds it together in such a way that it seems richer and

more complex than before.

© dirkdietrichhennig.com 2024